Definition

In corneal transplant, also known as keratoplasty, a patient's

damaged cornea is replaced by the cornea from the eye of a human cadaver.

This is the most common type of human

transplant surgery

and has the highest success rate. Eye banks acquire and store eyes from

donors to supply the need for transplant corneas.

Purpose

Corneal transplant is used when vision is lost because the cornea has been damaged by disease or traumatic injury, and there are no other viable options. Some of the conditions that might require corneal transplant include the bulging outward of the cornea (keratoconus), a malfunction of the cornea's inner layer (Fuchs' dystrophy), and painful corneal swelling (pseudophakic bullous keratopathy). Other conditions that might make a corneal transplant necessary are tissue growth on the cornea (pterygium) and Stevens-Johnson syndrome, a skin disorder that can affect the eyes. Some of these conditions cause cloudiness of the cornea; others alter its natural curvature, which also can reduce vision quality.Injury to the cornea can occur because of chemical burns, mechanical trauma, or infection by viruses, bacteria, fungi, or protozoa. The herpes virus produces one of the more common infections leading to corneal transplant.

Corneal transplants are used only when damage to the cornea is too severe to be treated with corrective lenses. Occasionally, corneal transplant is combined with other eye surgery such as cataract surgery to solve multiple eye problems with one procedure.

Demographics

The Eye Bank Association of America reported that corneal transplant recipients range in age from nine days to 103 years. More than 40,000 corneal transplants are performed in the United States each year. The cost is usually covered in part by Medicare and health insurers, although the patient might be required to incur part of the cost for the procedure. All eye tissue is donated. It is illegal to buy or sell human tissue.Description

The cornea is the transparent layer of tissue at the front of the eye. It is composed almost entirely of a special

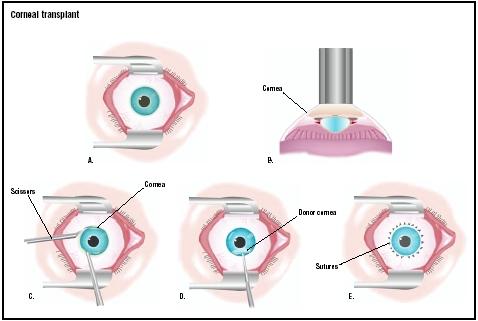

In a corneal transplant, the eye is held open with a speculum (A). A

laser is used to make an initial cut in the existing cornea (B). The

surgeon uses scissors to remove it (C), and a donor cornea is placed

(D). It is stitched with very fine sutures (E).

(

Illustration by GGS Inc.

)

The donor cornea is attached with extremely fine sutures. Surgery can be performed under anesthesia that is confined to one area of the body while the patient is awake (local anesthesia) or under anesthesia that places the entire body of the patient in a state of unconsciousness (general anesthesia). Surgery requires 30–90 minutes.

Over 90% of all corneal transplants in the United States are PK. In lamellar keratoplasty (LK), only the outer layer of the cornea is removed and replaced. LK has many advantages, including early suture removal and decreased infection risk. It is not as widely used as PK, however, because it is more time consuming and requires much greater technical ability by the surgeon.

A less common but related procedure called epikeratophakia involves suturing the donor cornea directly onto the surface of the existing host cornea. The only tissue removed from the host is the extremely thin epithelial cell layer on the outside of the host cornea. There is no permanent damage to the host cornea, and this procedure can be reversed. This procedure is mostly performed on children. In adults, the use of contact lenses can usually achieve the same goals.

Diagnosis/Preparation

Surgeons may discuss the need for corneal transplants after other viable options to remedy corneal trauma or disease have been discussed. No special preparation for corneal transplant is needed. Some ophthalmologists may request that the patient have a complete physical examination before surgery. Any active eye infection or eye inflammation usually needs to be brought under control before surgery. The patient may also be asked to skip breakfast on the day of surgery.Aftercare

Corneal transplant is often performed on an outpatient basis, although some patients need brief hospitalization after surgery. The patient will wear an eye patch at least overnight. An eye shield or glasses must be worn to protect the eye until the surgical wound has healed. Eye drops will be prescribed for the patient to use for several weeks after surgery. Some patients require medication for at least a year. These drops include antibiotics to prevent infection as well as corticosteroids to reduce inflammation and prevent graft rejection.For the first few days after surgery, the eye may feel scratchy and irritated. Vision will be somewhat blurry for as long as several months.

Sutures are often left in place for six months, and occasionally for as long as two years. Some surgeons may prescribe rigid contact lenses to reduce corneal astigmatism that follows corneal transplant.

Risks

Corneal transplants are highly successful, with over 90% of the operations in United States achieving restoration of sight. However, there is always some risk associated with any surgery. Complications that can occur include infection, glaucoma, retinal detachment, cataract formation, and rejection.Graft rejection occurs in 5–30% of patients, a complication possible with any procedure involving tissue transplantation from another person (allograft). Allograft rejection results from a reaction of the patient's immune system to the donor tissue. Cell surface proteins called histocompatibility antigens trigger this reaction. These antigens are often associated with vascular tissue (blood vessels) within the graft tissue. Because the cornea normally contains no blood vessels, it experiences a very low rate of rejection. Generally, blood typing and tissue typing are not needed in corneal transplants, and no close match between donor and recipient is required. However, the Collaborative Corneal Transplantation Study found that patients at high risk for rejection could benefit from receiving corneas from a donor with a matching blood type.

Symptoms of rejection include persistent discomfort, sensitivity to light, redness, or a change in vision. If a rejection reaction does occur, it can usually be blocked by steroid treatment. Rejection reactions may become noticeable within weeks after surgery, but may not occur until 10 or even 20 years after the transplant. When full rejection does occur, the surgery will usually need to be repeated.

Although the cornea is not normally vascular, some corneal diseases cause vascularization (the growth of blood vessels) into the cornea. In patients with these conditions, careful testing of both donor and recipient is performed just as in transplantation of other organs and tissues such as hearts, kidneys, and bone marrow. In such patients, repeated surgery is sometimes necessary in order to achieve a successful transplant.

Normal results

Patients can expect restored vision after the healing process is complete. In some patients, this might take as long as a year. Patients with keratoconus, corneal scars, early bullous keratopathy, or corneal stromal dystrophies have the highest rate of transplant success. Corneal transplants for keratoconus patients have a success rate of more than 90%.Morbidity and mortality rates

While there is risk involved with any surgery, corneal transplants are relatively safe. In 2001, there was some concern about cornea donors transmitting Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a fatal bone-deteriorating disease, after questions of infection arose in Europe. A study showed the risk of transmission in the United States was small, as was any infection risk from cornea donors. Currently, cornea donors are screened using medical standards of the Eye Bank Association of America. These guidelines restrict donors who died from unknown causes, or suffered from immune deficiency diseases, hepatitis, and other infectious diseases.Transplant recipients may have to receive another transplant if the first is unsuccessful or if, after a number of years, the disease returns.

Alternatives

An increasingly popular alternative to corneal transplants is phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK). This technique is now used to treat corneal scars and dystrophies, and some infections. Surgeons use an excimer laser and a computer to vaporize diseased tissue, leaving a smooth surface. New tissue begins growing immediately and recovery takes only a few days. Patients must be carefully selected, however, and success is greatest if damage is restricted to the cornea's top layer.Intrastromal corneal rings are implantable devices that could be used for some keratoconus patients. The rings are implanted and the procedure is reversible. However, not much is known about long-term stability. Some companies also are developing synthetic corneas that are implanted using synthetic penetrating keratoplasty. This procedure may become more widely used for high-risk patients and those with severe chemical burns.

WHO PERFORMS THE PROCEDURE AND WHERE IS IT PERFORMED?

Corneal transplants are performed by an ophthalmologist, who is a corneal specialist and is expert at transplants and corneal diseases. Patients might be referred to a corneal specialist by their ophthalmologist or optometrist.

Surgery is performed in a hospital setting, usually on an outpatient basis. Some surgeons may also perform the procedure at an ambulatory surgery center designed for outpatient procedures.

Esa

es la teoría básica detrás del entrenamiento locomotor (mediante input

sensorial del pie apoyado en la cinta rodante) y de estudios recientes

de la estimulación epidural de la médula espinal junto con actividad,

que llevan a la recuperación motora. La médula espinal no es un conjunto

pasivo de nervios, sino que es inteligente. ¿Pero cómo lo logra? Si los

científicos logran realmente entender cómo se comunica la médula, y si

esas redes entre neuronas se pueden expandir o modificar, tendremos

nuevas estrategias hacia la recuperación funcional tras una lesión o

enfermedad.

Esa

es la teoría básica detrás del entrenamiento locomotor (mediante input

sensorial del pie apoyado en la cinta rodante) y de estudios recientes

de la estimulación epidural de la médula espinal junto con actividad,

que llevan a la recuperación motora. La médula espinal no es un conjunto

pasivo de nervios, sino que es inteligente. ¿Pero cómo lo logra? Si los

científicos logran realmente entender cómo se comunica la médula, y si

esas redes entre neuronas se pueden expandir o modificar, tendremos

nuevas estrategias hacia la recuperación funcional tras una lesión o

enfermedad.